Merthyr Tydfil is one of my other interests, because of family connections and most importantly a great-great-uncle, D.B. Davies, who played rugby league for Merthyr and Wales in the early 1900s.

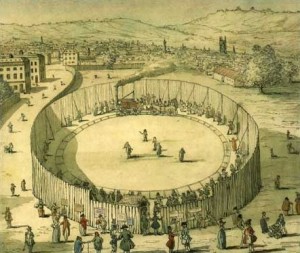

(D.B. stands for Dai ‘Brecon Road’ Davies, to distinguish him from the other Dai Davies on the Merthyr team; here are some old photos of Brecon Road, Merthyr Tydfil.) Merthyr is a place with an extraordinary history — one of the centres of the industrial revolution, site of the biggest iron works in the world, the first workers’ uprising in Britain, early trade unionism, and one of the first two constituencies to elect a Labour MP (Keir Hardie), it was an important place in the development of both the workers’ movement and industrial capital. It’s also famous for producing Wales’s two best-known historians, Gwyn Alf Williams (of whom more later), and Glanmor Williams, as well as Bill Roberts, builder of the first Daleks. There’s a UCL connection, in the form of Richard Trevithick, who built a high-pressure steam engine and turned it into a locomotive at the Penydarren Ironworks in 1802, and in 1808 opened to the public (to limited interest, by all accounts) a circular steam locomotive, Catch Me Who Can, on the site of the present Chadwick Building, by Gower Street.

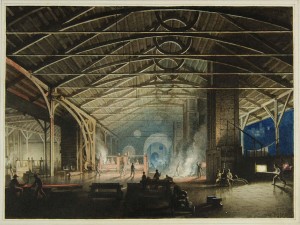

But even though Merthyr was once the most cosmopolitan place in Wales, I didn’t really anticipate finding a Russian connection, until I picked up a rather interesting little book in Church Street bookshop, Stoke Newington: Colin Thomas, Dreaming a City: From Wales to Ukraine (Ceredigion: Y Lolfa, 2009). This is the story of John Hughes, who started out as an apprentice at the Cyfarthfa Ironworks in Merthyr.

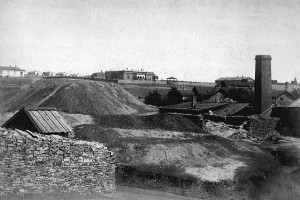

He became an factory owner and armaments manufacturer, and in 1870 moved to Russia and set up the New Russia Company, opening an ironworks in the Donbas. The town that grew around the works was called Yuzovka (Hughesovka), and the Hughes family made their home there, as did many Welsh workers who moved out to the Ukraine with their families to work at the plant.

Iron and steel production, and coal mines to supply them, grew steadily, and by 1905 Yuzovka had 50,000 inhabitants, one fifth of whom worked for the New Russia Company. The Soviet author Konstantin Paustovsky worked at the steel works during World War I, and Khrushchev was a member of the Yuzovka soviet after the February revolution, although according to Thomas’s account Bolsheviks were few on the ground even after the end of the civil war. In 1924, Yuzovka was renamed Stalino (not after Stalin, but meaning ‘town of Steel’). Vassily Grossman also started his work life in the town, as a mines inspector and chemistry teacher, before he became a writer. In many ways it seems to have become a very average town. In the Stalin era, it saw its share of the horrors inflicted on the country, by both the Soviet state — collectivization famine and terror — and Nazi occupation — 3,000 died in the Jewish ghetto, and over 90,000 were killed in the concentration camp there. In 1961 it was renamed Donetsk and went through the Thaw, stagnation, glasnost’ and post-Soviet deterioration like everywhere else. The population is now around 1.1 million, and it remains a major centre of heavy industry and coal mining. I don’t know why one should imagine that somewhere that has unusual origins should somehow remain exceptional, but it does seem slightly strange that it’s so normal.

The other thing that’s interesting about the book is that it also becomes a kind of biography of the (Merthyr-born) Marxist historian Gwyn Alf Williams, as the author worked with him on the production of various documentaries, including a short BBC2 series on Yuzovka in 1991 (which comes on DVD with the book). Williams was radicalized at a very early age, volunteering to fight in the Spanish Civil War for the International Brigade before he was in his teens (he was turned away) and, as many on the left did, revered the Soviet Union. Dreaming a City charts his gradual disillusionment, and as it shifts away from its initial focus on one side of Welsh-Russian/Ukrainian relations — the Hughes family and the development of the town of Yuzovka — it then turns into another, becoming a story about attitudes towards the USSR, in which the figure of Gwyn Alf Williams individualizes the problem of the European Left in a very moving way.